VTAAP Spotlight: Ballad Singing, West Glover, VT

Master Artist: Lorraine Hammond

Apprentice: Grant Cook

Traditional Art Form: Unaccompanied Ballad Singing

This is the final spotlight featuring artists who were part of the 2023-2024 cohort of the Vermont Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program, which included 18 collaborations between master artists and apprentices who are working together to keep traditional cultural expressions vital and relevant to the communities that practice them. The 2024-2025 cohort has just been announced! We look forward to featuring these artists over the next year.

With funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and a longstanding partnership with the Vermont Arts Council, Vermont Folklife initiated this program in 1992 to support the continued vitality of Vermont's living cultural heritage. In this ongoing series of Field Notes we’ll introduce you to some of the program participants and the traditional art forms they practice. Vermont Folklife has been documenting the work of participants in the Apprenticeship Program since its inception. These interviews and audio-visual records are part of an ongoing collection in our Archive centered around traditional arts, music, and trades.

Lorraine Hammond and Grant Cook spent their apprenticeship year exploring the practice of unaccompanied ballad singing, in particular drawing inspiration from the singing of Oscar Deegrenia. Lorraine’s family were neighbors of Oscar’s, and she grew up hearing his songs. Lorraine has dedicated much of her life’s work to supporting and engaging with traditional song, making her a perfect mentor for Grant to learn with.

Many singers also learn ballads by listening to “source recordings.” These field recordings are often made by folklorists, ethnomusicologists and others seeking to document regional music or a family lineage of traditional song. As a part of their apprenticeship, Lorraine and Grant listened to recordings of Oscar from the 1940s and 50s made by ballad collector Helen Hartness Flanders, and now held in the Helen Hartness Flanders ballad collection at Middlebury College Special Collections. Through these archival recordings, Grant was able to connect directly with a singer who deeply influenced Lorraine, bringing two generations of singers together to pass on their skills to the next.

Notes and recorded media from the Margaret MacArthur collection housed in the VT Folklife Archive.

Vermont Folklife’s own archive holds a related collection created by Margaret MacArthur of Marlboro, VT. Margaret was a singer herself who conducted fieldwork with the goal of learning Vermont songs directly from the people who sang them. When Flanders retired from fieldwork in the early 1960s, Margaret picked up the mantle and spent the next ten years documenting Vermont song. In the early 2000s Margaret donated her collection to the VT Folklife Archive, and you can browse the Margaret MacArthur collection here in our digital repository.

This note features interview excerpts recorded during a recent “virtual” site visit by VT Folklife staffer Mary Wesley where Grant and Lorraine discuss their work together. The interview has been edited for clarity and readability.

Lorraine Hammond I'm Lorraine Lee Hammond, born and raised in West Cornwall, Connecticut. And how I became wound into this Vermont Folklife piece has to do with a man named Oscar Degreenia. He was born in the late 1800s in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, moved to Cornwall with his wife Etta, and her dad in 1932. My parents married in 1939 and also lived in West Cornwall. They were both orphans so I don't have that family traditional network of being a tradition bearer that way, but they grew very close to Etta and Oscar. Oscar was illiterate and Etta cooked and cleaned for people, as my mom did. And we were on a small farm on the Cornwall side of Sharon Mountain, near the Housatonic river.

He [Oscar] did not read or write and he worked with my dad on the farm. So I have family stories about this Vermonter. His own kids were not interested in his songs, and I'm a singer. I mean, I was one of those kids who just sang when I did the chores and picked up songs in the school yard. And I was born in 1944, so I'm history! I'll be 80 on November 11th of this year. So Oscar's family, having come to the town years before I was born, were part of my life. I went to school with generations of his family and listened to that music. That's it. That's my connection.

Grant Cook I'm Grant Cook from White River Junction, born and raised in Spokane, Washington, 27 years old. I'm an amateur musician and music teacher and aspiring independent folklorist, I suppose, with a background mostly in instrumental music. No formal training with singing a passion for all sorts of traditional and participatory music styles. Starting in high school with klezmer and Balkan music and in college quickly became more focused on participatory singing, especially shape note music and nigun singing. I went to grad school for musicology at Wesleyan and did fieldwork that focused on participatory singing, amateur and traditional singing traditions.

I did not grow up singing ballads, but became enthralled by them as soon as I heard a Jean Ritchie record. At first I sang ballads by myself, learned them from records of traditional singers from Appalachia, but also recordings in the Flanders collection, recordings of Sarah Cleveland. I did not realize until only a few years ago that in New England there were still people who grew up in communities, neighborhoods, where ballad singing was a normal part of everyday life and who actually remembered the ballads that they heard growing up. And this news came to me in the form of seeing and reading an interview online that Lorraine had done about her recent projects in West Cornwall.

So I sort of dropped everything and knew that I very much wanted to meet her and learn from her. And talk to her about her childhood and what it was like to grow up in that neighborhood and to sit on Oscar Degreenia's porch and listen to him sing these ballads. And actually learn the songs, as she did when she was young and sang them herself, as she's told me. I figured the best way to learn more about this tradition was to learn how to do it myself. How to actually at least try to be some kind of ballad singer and to try and learn how to sing them the way she grew up singing them, as she heard Oscar Degreenia sing them, which is unaccompanied. Never any instruments, just for solo voice. So in the fall of 2022 I called Lorraine and we arranged a meeting down at her house in Brookline. We met and she took me on as a student of unaccompanied ballad singing, and we've worked together ever since.

Lorraine Hammond: It was great. I came home—Bennett [Lorraine's husband] and I were off at some folk festival and came home to the message and I thought, "Well, I've never taught ballads in that way." There are ways in which some of this is now coming home to roost in a very difficult way for me because I'm so close to so many people. I love them so dearly. We've had time together, creative time together and then gone back to whatever we were doing. But the connection is so powerful. And as Bennett and I are aging, of course, so are our friends. And so there's a great deal of need right now. And learning how we're all going to be able to help one another and using the music as part of that. There's a tremendous comfort in this music.

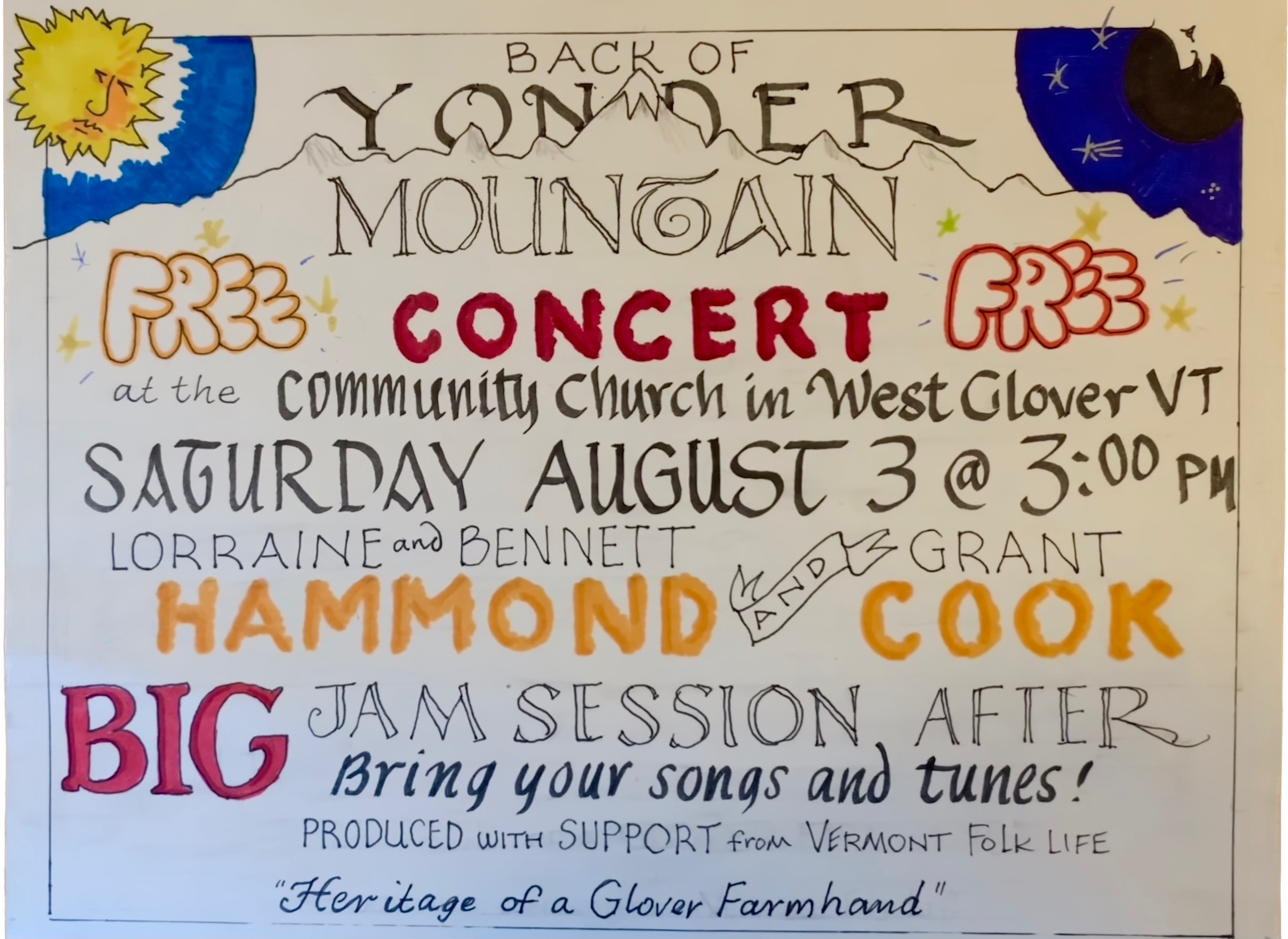

We [Lorraine and Grant] did a concert as part of our Vermont project and it was August 3rd, 2024, and we were in the meeting house at West Glover, Vermont. Those folks worked extensively to have that meetinghouse ready. It's beautiful, a place where people in the community have gathered for a very long time. And we did a program. My husband, Bennett, and Grant and I. And once again, when we sang the unaccompanied songs, people were engaged. And this ballad singing with root and power speaks... And Fair Fanny Moore was a ballad that Oscar sang, that I have never learned. It's beautiful, it has great language; it's a murder ballad. Grant has been willing to learn it, and I asked him to sing it.

And it was very hard and you were magnificent. You were present, Grant, and there was a gasp in the audience just because we could hear this tragedy. And it was so immediate. So I think that there's something very powerful happening here when the music is present. We need to keep it going, whatever the format. So that people can again connect one-on-one with that music. And so we've been doing that and it's extraordinary.

Concert poster advertising Grant and Lorraine’s final concert, along with Lorraine’s husband, Bennett Hammond.

Mary Wesley Lorraine, would you talk a little bit about how you approached teaching some of Oscar's repertoire to Grant? What goes into that process?

Lorraine Hammond Well, there are a couple that we kind of go for dibs on, because we love them. And we used the tape recorder. I sang and you recorded. There's a...Sheila Kay Adams, do you know that name? She's a seventh generation tradition bearer in North Carolina and a hot ticket. She's just great. And when she's teaching a ballad she talks about "knee to knee," and she's saying just sing it over and over, sitting together. So that was a piece of it. But I could sing something and it could be a month before we would be together. And I'm perfectly aware of the advantages of...YouTube may single-handedly save traditional ballads, you know! People can have a connection with somebody who sang and is no longer with us. And those are powerful. So I'm not against tape recorders as a way of getting a song.

But I think you [Grant] listen well. And that is as important as any other aspect for teaching. So if I were to sing:

Was in the springtime of the year, them flowers, they were blooming.

A young man on his dying bed in love with Mary Alling.

Slowly, she rose, slowly she rose, slowly she come nigh him,

When she got there young man, she said, I really think you're dying.

And then you would sing that. And the part that was the most interesting was to help Grant sing it like Grant. So that on the one hand, we want to honor the people we learn from. But then there is this question of mimic. And certainly in learning the old ballads I've heard people who would go back...and revival ballad singers will sometimes end up trying to sound exactly like a person. And it's often been taught that way. I don't buy it. I believe that the ballad itself has the power and that the singer will find that place in them that moves the ballad on. And that's tricky stuff. It's never been a formula for me at all.

Mary Wesley Grant, what was it like to receive this teaching? How was it on your side?

Grant Cook I mean, as Lorraine said it's very much just about listening. I would come prepared with three or four new ballads to sing and we might sing the whole thing beginning to end. And then maybe sing again, beginning to end. Just thinking about one aspect of the text or the tune, the breathing or the tone, the pronunciation that Lorraine suggests. And sometimes it would take narrowing it down to one stanza or one line, focusing on that line, that stanza, but we would rarely do that. More often Lorraine gives feedback that applies to the whole ballad. And more often it would really take singing the entire thing again. Understanding it as a whole. And understanding aspects of my voice, including things that I might not be aware of—where I'm breathing, the way I'm breathing, the way that certain words are coming out or not. Or it would often just be, as Lorraine said, you know, singing back and forth without even describing it. It's just listening and then singing it back.

And we would also listen to Helen Flanders' recordings, or field recordings of Oscar. Listen to them together, listen to the whole thing and then try and describe what he does. And as Lorraine says, not try to sing exactly the way he does, nor sing it exactly the way that she does. But at least start to try and understand how it works, which is still mysterious. You know, it's a really powerful style of singing. You'd think it would be simple—it's just one voice. But to wrap my head around how exactly a traditional singer like Oscar or like Lorraine actually pulls it off...it's really hard to pin it down.

Lorraine Hammond Another piece I think is worth putting in this interview so that it's on the record. Oscar's material had been collected by Helen Flanders. And my story, although we have not been able to document it except for Oscar's daughter, Dolly saying it, telling us. It was Mary on the Wild Moor. And Helen Flanders, we think, put in a column in her newspaper about one verse, Mary on the Wild Moor, because Dolly's story is, she saw it in the Waterbury Republican. Oscar didn't read or write, but she told him about it and said, "Why don't we give them the rest of the words?" And then she would do it. She talked about how hard it was. She'd forgotten how many verses there were. And she wrote it out longhand after she did her homework each night until she had it and submitted it. Helen Flanders appeared very quickly when she realized she had another ballad source. And so that relationship developed. But it was tough. And Oscar, like so many ballad carriers, came to distrust her. And now we get into the class...her background, and apparently she was pretty crunchy some of the time.

But when Oscar stopped singing for her and she passed on her collection to Middlebury College, for 50 years Oscar's family, after his death, would come from time to time and actually visit Middlebury, which was tough. They were not comfortable in that setting. And they would ask, "Can we have a copy? Can we hear it?" And were told, no this is the property of Middlebury College. It used to make me so angry that I finally went and got a masters. I got an independent study and the first thing I put into my study was the archiving—special collections. And I went and met with Andrew Wentink who at the time was special collections director at Middlebury, and I got that material released. And we were able to bring a CD to Dolly. She hadn't heard her father's voice in 50 years, you know? So we had so many layers to all of these stories.

[ Middlebury College Special Collections has since made much of the Flanders collection available via the Internet Archive. ]

Mary Wesley That’s such important work Lorraine. Grant, I wonder if you might share just a little bit about your final concert. It was wonderful to read the newspaper article that you forwarded. Would you just talk a little bit about how that concert came together and why you wanted to do it?

Grant Cook Sure. This was the second concert that I've done with Lorraine. The first was in October of last year in West Cornwall, Lorraine and Bennett have done this concert series in West Cornwall, to present concerts that bring back this music to the place that it came from. Music as well as, and even more importantly, the stories and memories of the people from that place who sang this music in this way. And so this concert in West Clover was similar to what Lorraine has been doing in Cornwall, Connecticut. West Glover borders towns where Oscar Degreenia grew up. He was born in Sheffield in 1878 and raised in a log cabin in Barton and worked for many years in Glover and West Glover as a farmhand. And Lorraine of course has maintained a constant connection with Glover and with the Northeast Kingdom. This was a chance for us to present an educational concert that was really focused on Oscar Degreenia, on his ballads and on Lorraine's memories of him and on what we know about him and his life and his songs.

It was a very community focused event. Brought together folks from all walks of life local to Glover and folks coming in from elsewhere, visiting. Including many people who have lived in Glover their whole life and. So the program had Lorraine and Bennett singing some of Oscar's songs in arranged versions with dulcimer and guitar and banjos, and a few of Oscar's ballads sung by me, unaccompanied, as well as some of Lorraine Lorraine's original songs that she's written about Cornwall, about family and community.

After this sort of informal concert there was singing and storytelling and a little bit of local history. And we finished with a jam session in the church basement with everyone bringing in whatever instrument they know how to play and bringing whatever songs and tunes they know how to play and just getting together and spending an hour singing and making music all together.

Lorraine Hammond It was wonderful. I had a great time. It was too hot. And we could not have the fans, which are noisy when we sing because you couldn't hear our words. We didn't have a sound system. We felt very present with the audience. But it was wicked humid. Not down in the church basement, which was kind of dank, but cooler. And my real belief is that by modeling, when we do these concerts, we always have a jam session after. That's keeping it alive and moving it forward.

Mary Wesley Grant, what are you thinking of, looking forward from here after a year-plus of learning the stuff?

Grant Cook The plan so far is to just not stop learning and to continue working with Lorraine as often as we can. To continue trying to figure out how to do what these ballad singers do, and to keep learning more. Keep singing—not in formal concerts or big stages or on records, but just in everyday life.